6.6 Society after

extinction of Buddhism

The

Indo-Aryan society of Vedic era was divided broadly in four Varnas which

basically represented the occupational affiliation of its populations. However

when Vedic era ended and the Brahmanism started flourishing, the first three Varnas

increasingly became synonymous with those populations who followed the concept

of Brahmanism. Shudra Varna started becoming synonymous with those populations

who followed anti-Brahmanic faiths and also included population of all other human

races or groups. In between the two, there were populations who were termed as

Vratyas. These were the populations of Indo-Aryan society who followed Buddhism,

Jainism, Shaivism and many other cults without abandoning their Brahmanic rituals

completely. Between 7th and 13th centuries AD, when

Buddhism as a faith was getting extinct because of various socio-political

conditions and Hinduism was evolving as a fusion of all orthodox cults,

followers of the former took refuge in the broader Hindu society. The merger

process, however, never resulted in homogeneous society and the differences

remained between the orthodox class of Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas and their

Buddhist or Jainist Vratya counterparts. Therefore in the medieval period, when

contemporary Hinduism was taking its shape, all orthodox or priestly Brahmins

irrespective of their race, location and cult formed mainstream Brahmin class

across northern-India. The Vratyas or non-priestly Brahmins got secondary

status in society. However in both groups, the individual clans maintained

distance with the others based on the spiritual sect, region they belonged and

physical attributes which basically represented the different human races their

ancestors came from i.e. broadly Indo-Aryan, Dravidian and Mongoloid. On

population front, both groups of Brahmins could have contributed equally in the

states of Bihar and Maharashtra. In the states of Bengal and Orissa of the eastern

India, which for prolonged period remained a Buddhist center, the Vratya

Brahmins could have formed large population of the Brahmin class with priestly

Brahmins forming a minor population but occupying greater social status than the

former one. The situation in southern India was however different and the

process resulted in the formation of three classes of Brahmins – the orthodox

Brahmins worshipping Vishnu, the orthodox Brahmins worshipping Shiva and the

non-priestly Brahmins who again represented the Vratyas. The difference between

north and south Indian Brahmin society has its origin in the period of Guptas

when complete assimilation of the Shaivite priestly classes took place with the

Vaishnava priestly classes across northern India. As south India was outside

the dominion of the Guptas, the Vaishnava priestly populations, majorly originating

from the Indo-Aryan group of humans, continued to maintain a distance with the Shaiva

priestly populations, majorly originating from the Dravidian race of humans.

In

Kshatriya populations, similar to Buddhist Brahmins, few who never left their Brahmanic

rituals completely even after adopting Buddhism, retained their Vratya Kshatriya

status in view of orthodox Brahmins after the extinction of Buddhism. This is

evident from the example of Gupta King Samudragupta who ruled from 335-375 AD and

proudly referred himself as Lichchhavidauhitra

(son of a Lichchhavi clan’s daughter). It must be noted that the Lichchhavis were

known to patronize Buddhism and Jainism. As per the commentary of Buddhaghosa in Sumangala-Vilasani, the

tribe never left their old Brahmanic faith completely. As a result, Manu

referred them as Vratya Kshatriya in the Manusmiriti. Clearly the Gupta kings never

considered the Vratya Lichchhavis as lower in social hierarchy when Brahmanism

was reviving under their patronage. It can be therefore said that many of the

Vratya Kshatriyas who patronized both Buddhism and Brahmanism simultaneously,

could have formed certain communities in the contemporary Hinduism who had an ambiguous

position in the caste hierarchy with no social relations with the Brahmanic

Kshatriyas / Rajputs. However, most Buddhist Kshatriyas who abandoned their Brahmanic

rituals completely for a prolonged period were tagged to Shudra Varna by the orthodox

Brahmins. This way after the extinction of Buddhism, the entire political class

of Indo-Aryan dominated society was divided into three categories – mainstream

Rajputs/Kshatriyas, Vratya Kshatriyas placed below Rajputs and the fully

degraded one as part of Shudras. Though religiously degraded to the level of

Shudras, still most of them maintained their dominance over society in the regions

where the orthodox Brahmin supporting Kshatriya or Rajput population was

negligible. It thus seeded the birth of economically sound castes / communities

in Shudra Varna in those regions and the scenario could have widely prevailed

in regions like Bihar, Bengal, Orissa, Maharashtra and Gujarat. In southern and

eastern India, as most of the political class had their origin from the Dravidian

and Mongoloid group of humans except few migrated Indo-Aryans and also followed

anti-Brahmanic cults, they were placed in Shudra Varna only. Similar to

Kshatriyas, was the case of Vaishyas across India. As there was strong punishment

advocated for all the three mainstream castes on violation of any Brahmanic rules

which even included involving in any laborious activity, few among them could

have seen their degradation to the level of Vratyas and even to the level of the

Shudras and outcastes from the period of the Guptas till British India. We,

therefore, are not surprised to find myth prevalent in certain communities in

northern India that how they were degraded from the rank of orthodox Brahmin or

Kshatriya when one of their ancestors used farming tool in the field due to

some emergency situation. It must be noted that in Brahmanism, agricultural

activity has been classified under Shudra activity.

Although

many orthodox Brahmins could have helped to merge the Buddhist population in the

contemporary Hinduism, still a large section of them could have been very

hostile towards the latter. The Vratyas of Brahmin, Kshatriya and Vaishya class

residing in the regions of Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar could have faced more

humiliation from the hand of orthodox than their counterparts living in the eastern

and southern India. This is because the former places saw a strong upsurge of

Brahmanism and remained the epicenter of that from the period of the Guptas

till modern era. The Vratyas of Brahmin class, who left their priestly

activities for a prolonged period under the influence of Buddhism, never got

their priestly rights again. Similarly, the Vratya Kshatriyas faced degradation

in their socio-religious position. However for Kshatriyas, tagged as Shudras,

the situation was worse. Being classified under the Shudra category, the orthodox

Brahmins refused to carry their Brahmanic rituals according to Kshatriya

tradition and that included the sacred thread and coronation ceremony. The very

hostile approach of orthodox Brahmins toward shudra classified Kshatriyas is

preserved in the history of 17th century Maharashtra. The event belongs

to none other than the great Maratha King Shivaji who founded the Maratha

Empire by fighting with Mughal Empire when most Rajputs/Kshatriyas of northern

India accepted the subordination of the Mughals. The entire event goes like

this -

The

discussion on the coronation of the Maratha leader Shivaji Bhonsle was started

in 1673 AD. However, the process got stuck as orthodox Brahmins refused to

accept him as Kshatriya and hence his rights to proceed with the coronation.

They argued with the help of shashtras

that only Kshatriya could be coronated and the Bhonsles are Shudras. Shivaji then

showed his lineage from the Sisodia Rajputs of Mewar. But orthodox Brahmins

maintained their position saying that the Kshatriya culture had vanished from

their families. Shivaji was not ready to accept this. He sent a delegation of

Brahmins under the leadership of Brahmin Balaji Aabaji to the centers of

Kshatriya customs, like Udaypur in Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh, to draw a

public opinion in his favor that the Kshatriyas still existed. Balaji Aabaji

was a progressive Brahmin and opposed to the orthodoxy and superstitions spread

in society. During their visit, they met Bhatt Brahmin family in Kashi who

originally hailed from the Paithan of

Maharashtra. One of the members of this family was Bishweshwar Bhatt (Gaga

Bhatt) who was a great scholar of his time and stood against orthodoxy. He

wrote several books and the contents were considered authentic looking at his vast

knowledge about Vedas, Smirtis and politics. Gaga Bhatt issued a certificate

stating that Shivaji is a descendant of the Sisodiya Rajput family (the clan of

Maharana Pratap) and therefore his coronation is in accordance with shashtras. He also held meetings with the

Brahmins opposing Shivaji’s coronation. He persuaded them to agree on the Kshatriya

lineage of Shivaji and in this process Balaji Aabaji supported him. Some

orthodox Brahmins got convinced. Shivaji was then first purified with holy

waters followed by putting on a sacred thread around the shoulders on 29th

May 1674. Before this, Shivaji was not wearing the sacred thread, a must for dwija castes and identification of a

person belonging to the upper three Varnas. After the thread ceremony, Shivaji

said: ‘Now I have become an upper caste. All upper castes have the right to

Vedas. The Vedic mantras should be chanted in all my rituals.’ At this, all

Marathi orthodox Brahmins got enraged and declared that the Kshatriya caste is

extinct in Kaliyuga. Now there is no

upper caste other than the Brahmins. Gaga Bhatt understanding the gravity of the

situation quickly completed the rituals without opposing them. In the next few

days, Shivaji’s marriage ceremonies with his queens were done again according

to the Kshatriya and Brahmanic rituals. The coronation was finally done on 6th

June 1674.

The

entire coronation episode clearly brings out the hostility of most orthodox

Brahmins towards shudra classified warrior populations. It can be easily

imagined that if a great King had to struggle to this extent in claiming

Kshatriya status for his coronation then what could have been the position of

normal Maratha people in view of the orthodox Brahmins? The answer of Brahmins

to Shivaji about the extinction of Kshatriyas in Kaliyuga only strengthens the

point that the Kshatriyas of Maharashtra were considered Shudras due to

non-compliance of various Brahmanic duties from unknown time. Resistance to

Shivaji’s coronation, the presence of lots of Buddhist caves and presence of

only two significant Varnas namely Brahmin and Shudra in Maharashtra (captured

in 1931 census) support the earlier point that how Buddhist Kshatriyas of the

region were considered Shudras after they merged with the contemporary Hinduism.

Did Gaga Bhatt’s certificate increase Shivaji’s or Maratha’s acceptability as

Kshatriya in Rajputanas of northern India? The answer is still negative. Except

some, most Rajput clans refused to enter into social alliances with any Maratha

clans who claimed the Kshatriya status (the 96 kula) after Shivaji episode. It must be noted that by doing his

coronation according to the Kshatriya tradition, Shivaji took a socially revolutionary

step and in the process offended the orthodox Brahmins. It cannot be,

therefore, ruled out that his future generations must have paid a heavy price

for the same.

After

the extinction of Buddhism, the Varna system of the Hindu society primarily represented

the followers or non-followers of Brahmanism and no longer represented only the

occupational affiliation of a given population or the human races from which

they originated. The same has been clearly captured in the caste based census

of British India. In the census data, the distribution of different Varna

populations across India reflects the same trend which is visible in the Vedic

literature. In the census, the regions which had large Dravidian, Mongoloid

and Negroid population and followed anti-Vedic faiths such as Buddhism, Jainism

and other aboriginal cults, show a higher Shudra Varna population that also

included despised and out-caste populations. On the other side, the epicenter

of Brahmanism and the settlement of Indo-Aryans i.e. Uttar Pradesh and

Rajasthan recorded the highest upper caste (Brahmin, Kshatriya & Vaishya)

population across India. The percentage upper caste population recorded decreasing

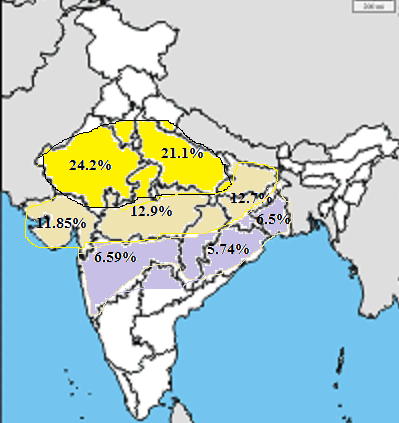

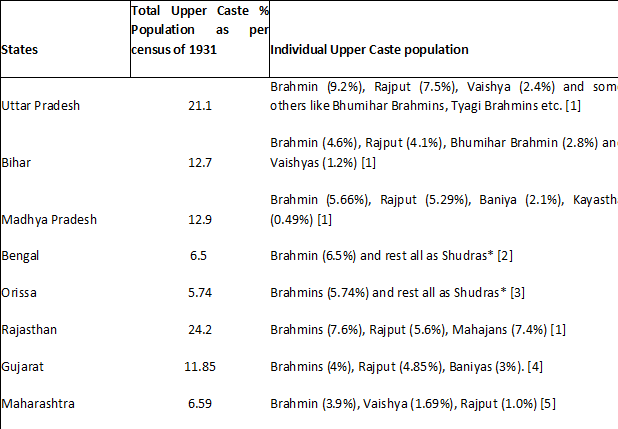

trend when moved into eastern and southern direction from these regions, refer Figure 6.6.1 and Table 6.6.1.

It must be noted that the Brahmin class and Brahmanic literature were used by the

Britishers to decide the caste of a particular family or community in the census.

As Britishers used the Brahmanic religious literature for classification of the

entire human population residing in the subcontinent, going by the same even

Britishers (or to that extent entire population of the world) could have been classified

as mlechhas; a very frequent word

used for the foreign tribes in Brahmanic literature with social position given

below or equal to Shudras.

Figure 6.6.1 - Upper caste population as per Indian Census of 1931.

Table 6.6.1 - The upper caste population of Indo-Aryan dominated regions

In

the entire mapping of human population on the Varna ladder, some communities

falling under the Vartya category were clearly captured by the census process.

In Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the census recorded a significant population of Tyagi

Brahmins (Taga) and Bhumihar Brahmins who have a lower status in the caste

hierarchy than the priestly Brahmins. It is well known that both were denied to

call them Brahmins for prolonged period indicating the hostility of orthodox

Brahmins towards them. The point here is that if this vast region has

population having sub-ordinate Brahmin status, then it should also have population

having sub-ordinate Kshatriya status. As Rajput and Brahmin population were

recorded nearly same in Bihar, it can be said that the population of Vratya

Kshatriyas was nearly same as that of Bhumihar Brahmins. In Maharashtra, which

too was a Buddhist center just like Bihar, a very faint population of the Kshatriyas

was recorded and their percentage was even lower than the Vaishyas. This land

also has a population of Chitpavan and some other communities who claim Brahmin

status, recorded as Brahmins in the census but had sub-ordinate status than the

priestly Brahmins. Here again, it can be said that the land of Maharashtra

should have a Vratrya class of Kshatriyas and in best estimates they could be

making 3-4% of the population of Maharashtra similar to Brahmins. However in

both states, such Kshatriya population was not captured indicating that they

were placed in Shudra class. It should be further noted that the shudra category

in Maharashtra was dominated by Maratha-Kunbis and the allied castes that made

31.1% of the entire population. The ethnographic literatures describe Marathas,

spread over Maharashtra and Konkan, as a heterogeneous category consisting of the

Marathas proper who formed an upper caste, the Maratha Kunbis who were

cultivators and other Maratha occupational castes. The first section consists

of three divisions, the pure one (asal or

Kuli), the illegitimate ones (denkhawala,

the Kharachi) and the mixed Marathas.

The asal Marathas did not practice

widow marriage, claimed Kshatriya rank, were inscribed to legendary 96 kuls and formed the social base for

Maratha Raj [6]. Today

almost all Marathas claim Kshatriya origin, however, it is worth to point out

that not all can be of Kshatriya origin as they constitute nearly 31% of total

Marathi Hindu demographics in Maharashtra and such a large percentage

population can not belong to the ruler or warrior class. The clubbing of such

large population under Maratha category only indicates that in view of orthodox

Brahmins, the society of Maharashtra had faint boundaries between its ruler

Kshatriya class (the land owners) and the land laborers or the other

occupational populations. On the eastern side, the states of Bengal and Orissa have

a majority population originating from the interbreeding of Dravidian and

Mongoloid races of humans and therefore non-Aryans. Both states recorded only

two Varna populations – Brahmins and Shudras. In Bengal, the Shudra population

was further divided into four categories – Sat-Shudra, Jalacharaniya-Shudras,

Jalabyababharya-Shudras and Asprishya-Shudras. Brahmins took water from the first

two sub-groups while did not take from the third group. The last one formed the

lowest in the social pyramid whose touch was considered sufficient to impure the

water of the Ganges. The political elite class of Kayastha belonged to Sat-Shudra

category [7]. Even though the Sat-shudras occupied superior

position amongst Shudras still their socio-religious position was not good in

the society of Bengal. It can be seen from the example of Swami Vivekananda, a

Kayastha by birth. Swami was manhandled near the Dakineshwar temple for the

reason that why a Shudra became monk which according to the scriptures, does

not have such rights [8]. It must be noted that Kayastha is a group of record keepers who came into

existence in medieval period and the population came into this profession from

different castes of society [9]. Going south, where the majority population belonged to the Dravidian race of

humans, the upper caste population was recorded around 4-5%. The upper castes

consisted of majority Brahmins with a minuscule population of Kshatriyas and

Vaishyas. In eastern and southern India, like northern India, the orthodox

priestly populations of all races and cults were recorded as Brahmin only. Overall

after the extinction of Buddhism, the northern India emerged as an example of the

four ladder Varna system while the eastern and southern India emerged as an example

of the two ladder Varna system. During the peak of Brahmanism, every powerful

community created fanciful stories about their origin with the help of orthodox

Brahmins. The stories were created in such a way that it traced their origin

directly to early Vedic society with no Buddhist (or Jain) trace. The process

happened in most human groups irrespective of whether they lived in the north

or south, followed the orthodox or heterodox cults, belonged to the Kshatriya

or Brahmin clans and originated from the Indo-Aryan or Dravidian or Mongoloid

races of humans. Interestingly most populations having the sub-ordinate status

than the priestly Brahmins and Rajput / Kshatriyas, traced their origin from the

events associated with the mythical Brahmin figure Parashurama. Going through the

socio-historical development, it can be said that most of these legends justifying

the sub-ordinate status of a particular human group had been created in the medieval

period to erase one’s Buddhist or Jain linkage and thus getting the Brahmanical

holiness. Many of these legends were recorded in the early census and the Britishers

were amused after knowing them. Today, Shudra populations are generally

confused with only outcastes and the other despised castes. In Independent

India, the Shudra class is broadly divided into backward castes and out-castes. Backward castes are further divided

broadly into two groups- forward castes (part of open / general category) and

other backward castes (OBC). Forward castes basically represent the socially dominant

population of a particular region, who were considered and positioned as

Shudras in society and census by orthodox Brahmins. These forward castes are

mostly found in Gujarat, Maharashtra, Orissa, Bengal and South India. The Kayasthas

of Bengal and Orissa, the Patels of Gujarat and the Marathas of Maharashtra are

typical examples of the forward castes amongst Shudras. The forward castes were

denied reservation in government job and education like upper caste populations

and their Vratya counterparts. The classification of forward castes in open / general

category had led to a broader confusion in society about the total strength of the

Shudra population in a particular region. Many a times it is found that these

forward castes use the same hatred arising out of the chatur-varna system towards other communities of Shudra Varna forgetting

that the same was once used against their ancestors that included Shivaji and as

early as Swami Vivekananda. It is also interesting to note that when some of

these forward castes opposed their classification under Shudra category and

wanted to be recorded as ‘Upper Castes’ in British India, now many of them are

demanding an OBC status from Govt. of India and some of them have got too. It clearly

reflects the churning in Hindu society in which both ‘caste system and false

pride associated with it’ are losing its importance against the economic

benefits associated with OBC status. Also the trend clearly supports the view

of many social-reformers who from time to time have advocated for educational

and economic soundness of women and Shudras to counter the challenges inherited

from the past by the Indian society.

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************

References:

[1] Jaffrelot,

C. (2003). India’s Silent Revolution: The Rise of the Lower Castes in

North-India, pp. 67-81, UK: C. Hurst & Co.

[2] Ghurye,

G. S. (1969). Caste and Race in India (5th Ed.). p. 393. Mumbai:

Popular Prakashan.

[3] Jenkins,

R. (2004). Regional Reflections: Comparing Politics Across India’s states, p.

115. India: Oxford University Press.

[4] Vora,

R. & Agnihotri, V. K. (2005). Socio-economic Profile of Rural India:

North-central and Western India, p. 344. New Delhi: Concept

[5] Jaffrelot,

C. (2005). Dr. Ambedkar and Untouchability: Analysing and Fighting Caste, p.9.

UK: C. Hurst & Co.

[6] Singh,

K. S. (2004). People of India: Maharashtra, p. XL. Part I. Vol 30. Mumbai:

Popular Prakashan.

[7] Ghurye,

G. S. (1969). Caste and Race in India, p. 8. (5th Ed.). Mumbai: Popular

Prakashan.

[8] Ghosh,

G. K. & Ghosh, S. (1997). Dalit Women, p. 6. New Delhi: A.P.H.

[9] Sharma,

R. S. (2001). Early Medieval Indian Society: A Study in Feudalisation, pp.

194-196. (3rd Ed.). Hyderabad: Orient Longman.

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************

Index Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10

Give your feedback at gana.santhagara@gmail.com

If you think, this site has contributed or enriched you in terms of information or knowledge or anything, kindly donate to TATA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL online at https://tmc.gov.in/

and give back to society. This appeal has been made in personal

capacity and TATA MEMORIAL HOSPITAL is not responsible in any way.

********************************************************************************************************************

********************************************************************************************************************